RETURN TO HOME PAGE

FEEDBACK

|

March 2004

RETURN TO HOME PAGE FEEDBACK |

Leo Holub's Life in Pictures

By Rosie Ruley Atkins

Regular Noe Valley Voice readers probably think they know a lot about Leo Holub from reading his wife Florence's column, "Florence's Family Album," over the past 15 years. We know that Leo befriended a slug, named it Freddie (after a late family dog), and took great pains to avoid squishing it during nighttime visits to the kitchen. We know he once sported a beard that sparked great controversy. We know that every year on his and Florence's wedding anniversary, Leo winds up dinner with the question, "Well, want to try it for another year?"What the stories don't reveal is that Leo Holub, 87, is also one of the most noteworthy and influential artists of his generation and an avid chronicler of life in San Francisco. A photographer, Holub has exhibited his work at galleries around the world and has published an award-winning book.

Holub, who was born in Decatur, Ark., in 1916 and moved west to Oakland in 1923, attributes his success as an artist to his mother.

"She said I was always drawing things when I was little," Holub recalls. When Holub graduated from high school, it was his mother who sent out inquiries about art schools and determined that the famed Chicago Art Institute would be the best place for her son.

Holub worked for two years as a blacksmith's apprentice in the mines of Grass Valley, Calif., to finance his first year studying painting in Chicago, but it was an exhibit by photographer Edward Weston that exposed the young artist to his first "real photographs" and spurred his interest in photography as art.

After a year in Chicago, Holub returned to San Francisco and enrolled at the California School of Fine Arts (now San Francisco Art Institute), where he met and wooed Florence. Their first date, a visit to their art teacher in the hospital, ended with Leo treating Florence to a cab ride to her home in the Sunnyside District. "he must have thought I was a rich guy," Leo says of the extravagance that left him so broke that he had to walk home rather than take the streetcar. A year and a half later, in 1941, the couple married.

A designer by trade, Holub was already interested in photography when their first son was born in 1943. Today, Holub points to a portrait of his son and says, "That's what really got me going [with photography]. We had the most beautiful baby in the world."

By the time their third son was born, Holub had built a darkroom in their home and was using his design skills to create beautifully crafted bound volumes of family photos featuring each son.

After spending a couple of years in the Grass Valley area, where Leo's family lived, the Holubs returned to San Francisco, living in the cottage behind the paint shop that Florence's father owned in the Mission. In 1957, they bought the home on 21st Street where they still live today. They laugh when they talk about the bidding war they entered into when they bought the house. The other party offered $25 over the asking price, and Leo boldly upped the ante by $100. "And the place needed some work," he says.

Throughout the years, the Holubs remained involved in the artistic life of San Francisco, forging friendships and working collaboratively with their wide circle of friends, which included writer Wallace Stegner, artists Ruth Asawa, Frank Lobdell, and Nathan Oliveira, and photographers Imogen Cunningham and Ansel Adams.

It was under Adams' tutelage at his Yosemite workshop in 1956 that Holub's interest in photography as art was cemented. Upon returning to San Francisco, Holub began documenting the life of the rapidly changing city with his 4-by-5-foot view camera. His friendship with Adams also continued, with Holub designing Adams' 1963 book, An Introduction to Hawaii, and the catalog for Adams' 1963 show at the M. H. de Young Museum.

Typically modest about his ties with such creative luminaries, Holub says of his friends, "I knew they were famous, but we all just got together."

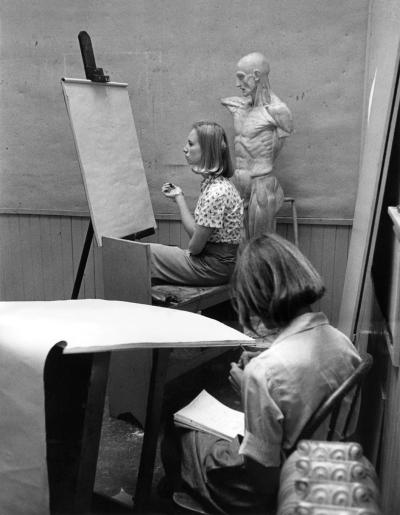

By 1960, Holub had landed a job in Stanford's planning office, where he was known for carrying his 35 mm camera around the campus, capturing vivid images of student life. When Lorenz Eitner, the chair of Stanford's art department, asked Holub to document the cramped quarters in which the art students worked, he hoped that the resulting photographs would support his case for building a new arts center on the campus. Unfortunately for Eitner, one hardly notices the cramped spaces when viewing Holub's photos from the project. Rather, their understated artistry captures the viewer's full attention. An image from a drawing class reveals the symmetry between an art student's pensive pose and an anatomic model's body; the stark angularity of a blank sketchpad contrasts with the curls of the student's hair and the ornate filigree of the cast-iron radiator. And while Eitner wasn't able to use the photos for their intended purpose, he did give Holub an acclaimed January 1964 show, "Stanford Seen," at the Stanford Art Gallery. "All the students came," Florence remembers. "It was just a wonderful thing."

Drawing class at Stanford University, 1963 A collection of Holub's images from that show reflects the organic, documentary quality of his approach to his photography. In one, dominated by the broad geometry of the roofs of Stanford's Inner Court, a solitary figure emerges from the shadow of a single tree. In another, the towering, fogbound eucalyptus trees of the Stanford Arboretum are lent perspective by a student rushing through the fog.

"My Stanford photos were what happened as I was walking between assignments," Holub says today.

Sitting in his comfortable, art-filled Noe Valley home, he still marvels at the progression of events that began with those Stanford photographs.

"Things happen to me. I've been receptive, but I've never gone out looking."

When Eitner's new art building was completed in 1969, he turned to Holub to create the university's first photography program. Holub built out the program's studios and darkroom facilities himself, calling upon the skills he'd picked up during his varied career, which included stints as a shiprigger, industrial designer, art director, and teacher. Once the program was launched, Holub remained at the helm for 11 years, building a program that became a central part of the California photography community.

Ansel Adams celebrated his 70th birthday in Holub's hand-built darkroom, and Imogen Cunningham presented seminars to Holub's students.

Holub's program, which focused on the development of the artistic eye more than on the mechanics of photography, was enormously popular, and Holub figures that he taught over 4,400 students.

Today, Holub stays in touch with many of his former students. One even sleeps on the sofa in the Holub living room when he visits San Francisco. "I guess I was like their favorite uncle," Leo says. "I feel like they were all my friends."

After retiring from Stanford in 1980 as Senior Lecturer Emeritus, Holub published a book, Leo Holub Photographer, which won 50 book-of-the-year awards and featured an introduction written by his old friend Wallace Stegner. During this period, Holub also mounted several successful shows in the United States, Europe, and Japan. But it was a photograph from his Stanford days that led to what he calls "a great project, a highlight."

In 1963, Holub photographed Richard Diebenkorn, who was then a visiting artist at Stanford. Holub's boss Eitner had given a print of the photo to Menlo Park residents Harry and Mary Margaret Anderson, whose noted collection of 20th-century American art includes work by Diebenkorn. Years later, when the Andersons hired a photographer to create a computerized archive of their collection, she came across Holub's portrait of Diebenkorn and recognized its artistic and documentary merit. The Andersons went on to commission Holub to photograph more than 100 artists represented in their collection.

The resulting portraits are remarkable as much for their natural composition as for the way in which they convey their subjects within the context of their work. Photographs of such art-world giants as Frank Stella, Wayne Thiebaud, Roy Lichtenstein, and Helen Frankenthaler reveal a rare candidness and comfort with the camera. In each portrait, the viewer feels treated to a revealing glimpse of how the artist creates and lives with his or her work.

"I went into their studios with no preconceived notions on what I'd do," Holub says. "I used existing light and photographed what I found." Holub's stunning results are likely a result of his straightforward approach. The painter/printmaker Pat Steir "told me that I was the first [photographer] who didn't ask her to move her furniture around."

Of an amused-looking Jasper Johns, Holub says simply, "We got along okay."

His portrait of minimalist painter Agnes Martin reveals a confident self-sufficiency that Holub says reminded him of his grandmother.

Over the course of the project, Holub forged friendships with many of the artists, and today work by Martin Puryear, Oliveira, and Diebenkorn hang alongside paintings by Florence and photos by Holub, Adams, and Cunningham on every wall of the Holub home.

These days, Holub spends much of his time in his garret-like top-floor office, which features the untouched web of a daddy longlegs spider that Holub considers a terrific officemate. The room is crowded with dozens of cartons of his own work and years of correspondence that he is archiving for donations to the Stanford Library and the Archives of American Art at the Smithsonian. Of the many art books that Holub keeps, one of his most treasured is a first-edition volume of pre-war work by Parisian photographer Eugene Atget, whose influence on Holub's eye is obvious.

Holub's downstairs darkroom and studio is a treasure trove of images organized by year in fireproof vaults. One file drawer contains the negatives from the 360 rolls of film he shot in 1967. A random search of a shelf results in a 1972 photograph of the San Francisco skyline, shot from China Basin. Crumbling wharves fill the foreground of the picture while a trio of under-construction skyscrapers, surrounded by skeletal scaffolding, illustrate the abrupt changes to the skyline that the period saw.

Another image of the rolling undeveloped hills of Twin Peaks is strikingly bucolic.

The 50 years of images of San Francisco reflect "whatever looked good at the moment," Holub says. "If the light was right, I took the picture."

The photos chronicle decades of changes in San Francisco's cityscape, depicting a time when Noe Valley was considered the "country" and the avenues of the Sunset were sand dunes.

For Holub, the pictures don't evoke a sense of change or nostalgia or regret for what came before. "When I'm taking a picture, I don't think about the past," he says. "Every time I photograph something, it's new."

Holub is still seeking the new. He takes a daily digital photograph of the sun rising, and as he clicks through the sunrise images on his Macintosh computer, one is struck by the minute changes that the daily view reflects.

Holub is also in the habit of carrying a small camera in his pocket with which he captures images that strike his fancy as he travels around the neighborhood.

"It's just something to get the urge [to take photographs] out of my system," Holub says, his index finger unconsciously triggering an imaginary shutter.

He shares a stack of his most recent pictures. A chorus line of vines tumbles over a mottled concrete wall. A dog stares mournfully from the sidewalk, his leash looped around a parking meter. A single tree rises from a square of mud and crushed cigarette butts.

Together, the photographs, which Holub, ever unassuming despite his abundance of talent, says he hasn't "found much use for," capture the essence of Noe Valley. They're the small pieces of neighborhood life that we notice only if we slow down and look in a different direction, the way Leo Holub does every day. m